Mississaugas were a people of the waters

Posted on November 21, 2022

By Darin Wybenga in partnership with Waterfront Toronto for National Day for Truth and Reconciliation

Mississaugas of the Credit ancestors arrived on the north shore of Lake Ontario at the close of the 17th century. Migrating from the north shore of Georgian Bay and Lake Huron, the Mississaugas dispersed the previous occupants of the land and erected their wigwams on the flats of rivers and creeks flowing into Lake Ontario. The Mississaugas were a people of the waters and, it is thought by some, their name “Mississauga” derived from the Anishinabek (Ojibway) word Minzazaheeg meaning “people living where there are mouths of many rivers”. Intimately familiar with the waters throughout their nearly 4000000 acre territory, they provided descriptive names to many of the waters flowing into Lake Ontario such as : Adoopekog,”place of the alders”, now known as Etobicoke Creek; Wonscotonach, “back burnt grounds” – the Don River, and the Missinnihe,”the trusting creek”, a favoured location for hunting, fishing, gathering, healing and spiritual activities that is now known as the Credit River. A seasonally migrant people, the Mississaugas often plied their canoes on the water as they purposefully moved about the land for sustenance. The waters provided a rich variety of aquatic animals and plants for food with perhaps salmon as the most important. At least twice a year, during the spring and fall, the Mississaugas would converge on their fishing grounds on the creeks to take advantage of the abundance of salmon. Spearfishing from their canoes at night with the aid of a torch, the Mississaugas would harvest and dry the fish that would sustain them during the winter months.

Recognizing that water was more than just a food source, the Mississaugas regarded the water as the life blood of mother earth. As the water circulated its way throughout their lands, the people recognized its life-giving properties and its powers to create and destroy. The re-creation story of the Mississaugas told of the cleansing power of the waters; the people saw with their own eyes Lake Ontario’s erosion of the Scarborough Bluffs and its simultaneous creation of the peninsula that would one day become Toronto Island. They even recognized the gentleness of water as it protected the unborn child in the womb of its mother. For the Mississaugas, water was, and is, a living spiritual being that flowed through all aspects of life. Water was not regarded as a stand alone entity, but seen as a vital part of a larger system whose components worked together harmoniously for the benefit of all. Water was to be thanked and treated with the utmost respect and care, it was not to be treated as a commodity. To be careless with the water and disregarding the gifts it provided would be dishonouring and destructive to it and to the ecosystem of which it was part. Back then, and today, the Mississaugas and other Indigenous people throughout the world hold ceremonies to thank the waters and show their reverence for its benevolence.

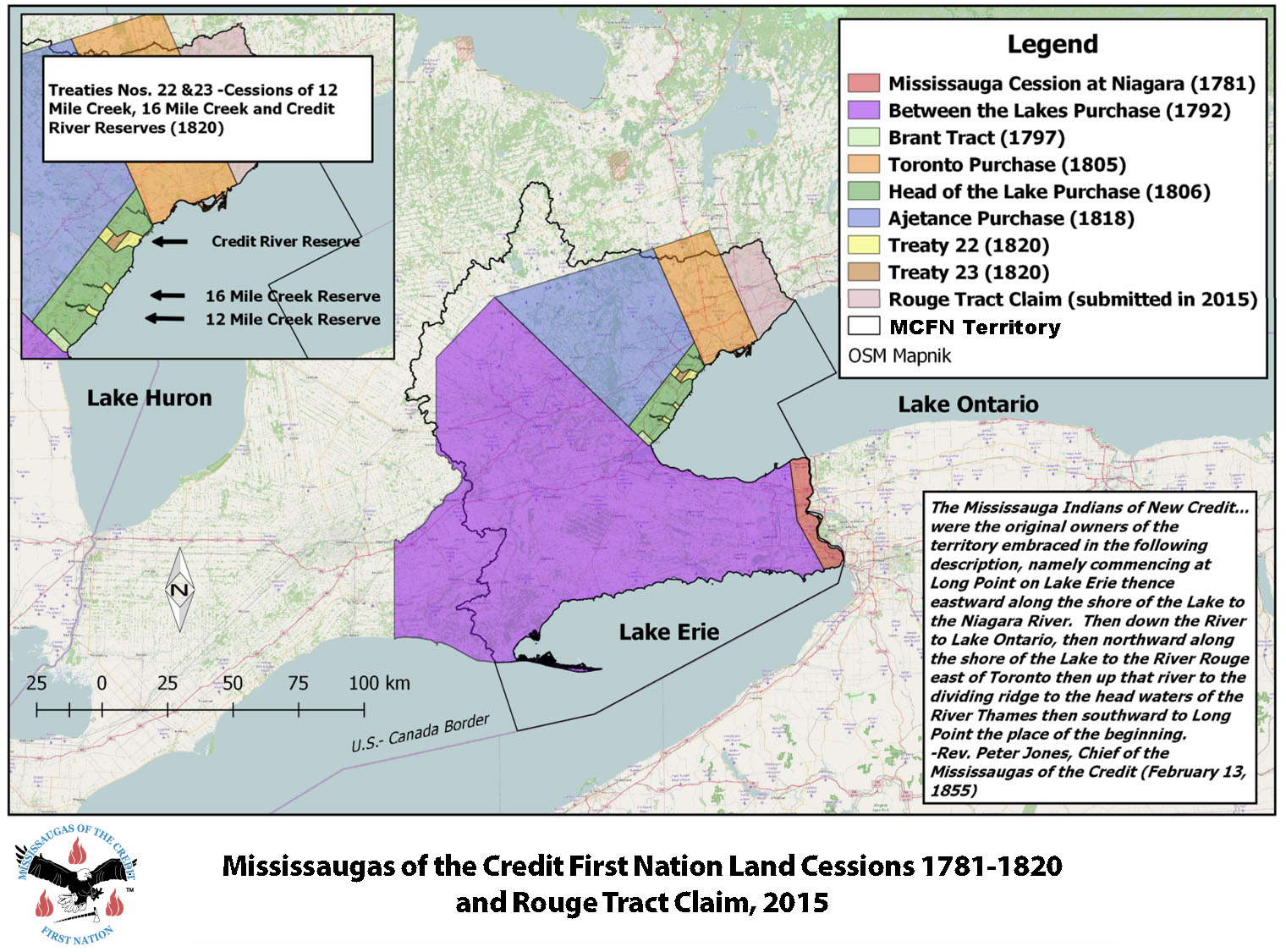

The treaty making period for the Mississaugas of the Credit lasted from 1781 to 1820. During this period, the Mississaugas gradually became alienated from the waters of their territory. Eight treaties with the Mississaugas opened their territory to settlement. An overwhelming influx of settlers brought a vision of stewardship that was far removed from that of the First Peoples. Water, in the eyes of the newcomers, was to be viewed as something inanimate, a commodity to be used to drive the mills they built, a place to harvest the salmon (to near extinction), and a place to dump refuse- all things dishonouring to the spirit of the water. and ultimately destructive to all beings on Turtle Island. The wholistic view of water and the harmony promoted by the First Peoples was swept away in the name of “civilization” or “progress”. The Mississaugas became strangers in their own land.

Now, some two-hundred and twenty years after the treaty making period ended for the Mississaugas, they are travelling with settler society on a path of reconciliation. One part of traveling the path involves both groups working together and devising a strategy that promotes the wise stewardship of water in the environment that they both inhabit. Environmental stewardship is a joint concern of both groups and the spirit of reconciliation can be nurtured by both groups focusing their attention to restoring a respectful, harmonious, and grateful relationship with water. For the Mississaugas, whose stewardship has been undermined by years of colonialism, how can they bring their insights to bear on issues and projects impacting the waters of their territory? For the settler population, who has long viewed water as a commodity, how can they restore water to a position of respect in a society largely driven by economic interests? There are no easy answers regarding environmental stewardship, or First Nation/settler reconciliation for that matter, but in order to avert disaster both groups must work together for the benefit of all. The road to reconciliation will be bumpy in some spots and smooth in others, but both groups, the Mississaugas and settlers, working together in a spirit of peace, friendship, and respect must collaborate together to restore harmony in the territory they share -their futures depend on it.